Roberto Fusco and Emma Fält – The Wave in the Mind, 2024

Before the advent of powerful computer and sensing technology, wave phenomena were only described and logged by visual observation and subjective evaluation of individuals. “The Beaufort scale, which is used in Met Office marine forecasts, is an empirical measure for describing wind intensity based on observed sea conditions.” Since the 19th century, the scale has become a standard for ship’s log entries.

The two videos are the result of a simulation of two storms:

Rafael on 22-Dec-2004 at 22:20 that happened in the Baltic Sea. The data relative to this sea condition, gently provided by the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI), were measured at the buoy in the Northern Baltic: 59°15´ N, 21°00´ E., close to the Suomen Leijona lighthouse. They feed a physically based mathematical model of wave motion and a computer program developed by Roberto to generate the 3d visualization.

The second storm was experienced by a Finnish vessel, Pommern on the 5th of March 00:00–4:00, 1934. For this event, only the human interpretation of the phenomena can be read on the ship logs, which are available from the digital archive of the Åland Maritime Museum.

Currently, an increased amount of data, in terms of time accuracy and spatial diffusion, more accurate mathematical models, and machines with increased computation power, allow scientists to more realistically describe and visualize phenomena and provide more accurate forecasts of meteorological events.

Simulation technology allows one to model and predict phenomena but also reconstructs events that we haven’t witnessed in the first place, first person. Here, thanks to the available historical data, the simulation is a time machine that creates narratives and writes stories of the past. It is a speculative recording, a sequence of images no camera has captured, only a buoy and its embedded sensors.

Computation shapes both the future of our experiences and our understanding of the past. The scale-model lighthouse in the middle of the room rhythmically investigates the space and presents us with glimpses of three touching horizons.

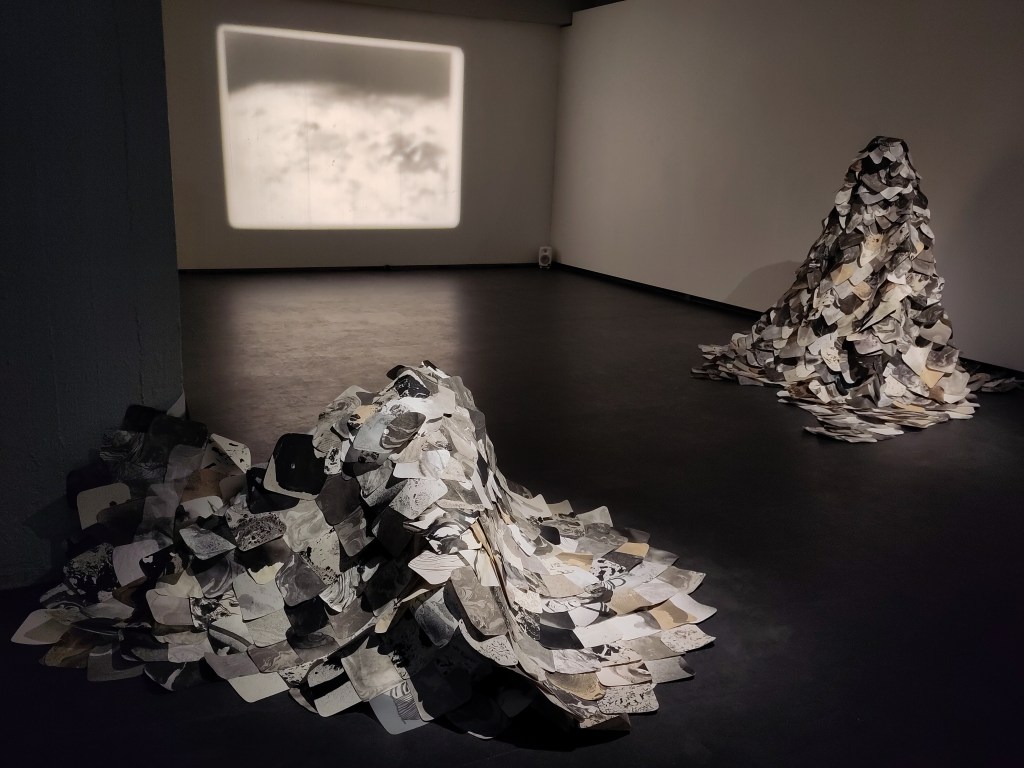

On the other hand, tactile sense and listening to matter through the human body can offer us different kinds of knowledge about the environment. The two big but fragile paper bodies are covered with hundreds of encounters, attempts to connect with water to understand how its movements move the being experiencing them. By using the old traditional printing technique, Suminagashi or “floating ink” on water, the prints appear different depending on the surface tension. Understanding the surface tension of water is important in a wide range of applications including heat transfer, desalination, and oceanography. Much we can observe just by looking at the surface, yet we know little about the life underneath the surfaces of different bodies, being it humans or bodies of water.

The soundscape is created by following the simulation of storm waves and recording the sounds by drawing them. Emma has been using different materials, pen on paper, paper on wood, metal on wood as well hands moving on different surfaces. Voice artist Anna Fält was connecting with the winds, the simulation as well as the little details of the waves using her voice. They wanted to use their bodies as instruments of “becoming another body” to attune with a body that is not human or even considered alive.

In the installation, the long gone, emerging, and invisible bodies connect, hide and cover as well as shelter. All the different patterns and waters are mixed and moving endlessly. Little do we understand all the connections between elements and natural forces. Right now, it seems more than important to think about our knowledge formation and boldly weave together different ways of exploring and understanding the world.

DATA as seeds of storytelling

For Rafael, on 22nd December 2004, the significant wave height in northern Baltic Proper reached 8.2 meters and the highest individual wave height was 14 meters. Toini, January 12th 2017 a similar significant wave height (8.0 m) was recorded. Sensing technology embedded in buoys provides detailed data at one point and time that allows researchers to simulate the overall aspect of the waves. The time series, that is the collected data in time, provides us with a timeline of what happened. This story is told in a language very few speak, which is difficult to understand but also very simple. Every sensing technology reduces a phenomenon under scrutiny to a few observable physical quantities. It is a reduction that leaves many things untold.

The animation presented in the digital projection and the laser engravings on paper are attempts to use the data through a physically-based inspired simulation, a mathematical model, a set of formulas, to give life to these stories.

Characterizing a complex phenomenon such as the sea state is prone to fail. It is in this impossibility that we can rediscover the meaning of experience over simulation, the articulation of material forces that cannot be reduced to equations and parameters.

When sensing technology was unavailable, a duration that encompasses most of the history of humankind, sailors used their observational skills to talk about the sea. Subjectivity was embedded in the handwritten logs of ships. For Pommern ‘34, only a speculative reconstruction of the storm was possible: to read and imagine, to fantasize about an experience and translate it into parameters of a computational model. These ship logs are data as well, they are snapshots of observations and felt experiences. The 16-mm film projection, realized in collaboration with live cinema artist Marek Pluciennik, translates an old story into an old medium, film, to remind us that the history of stories is also a history of the technology used to write and share them.

POMMERN SHIP JOURNAL 1934, 5th of March 00:00 – 4:00

p.8 rows 21-24

Tilltagande sjö, hårda byar, fartyget slingrar våldsamt, hög överbrytande sjö (det far över däck). 23.30 sprack stormast seglet på styrbord nock (längst ut på rån). Klara lantärnor (positionsljusen/navigationsljusen dvs styrbord babord)

– den gigades och seglet sviktades

—–

Strengthening sea, hard wind gusts, the ship meanders violently, high breaking sea. At 23.30 The main mast sail busted (square sails). The lanterns (positions lights) are undamaged.

– The sail was gigged and failed

p.9 rows 1-4

Ytterst hög och överbrytande sjö stordäck jämt fylld med vatten. Sjön bryter mycket svårt över halvdäck och brygga. Lucksurrningarna ännu oskadade

—-

Very high seas and breaking sea, main deck still full of water. The sea is breaking very violently over half deck and bridge. Hatch lashes are still unharmed.

p.9 rows 5-8

Vinden litet avtagande sjön bryter fortfarande svårt över, stordäcket jämt fyllt med vatten. Lucksurrningarna fortfarande oskadade. Länsat bort vatten från durkarna akterut.

—

The wind is slightly dropping, but the sea is still breaking violently over, the main deck is still full of water. Hatch lashes are still unharmed. Water is drained from the flooring in the aft.

List of works and layout

1 – Lighthouse, LED light, motor, 3D-printed PLA lamp case

2 – Bodies – paper sculpture, Suminagashi prints on recycled paper

3 – Rafael 2004 – data-driven simulation, digital projection

4 – Pommern 1934 – ship journal-informed speculative reconstruction of the storm on 16-mm projection

5 – Toini 2007, data-driven simulation, Laser-engraved print

6 – 4-channel sound from drawing on paper, wood and metal

THINGS NOT ACTUALLY PRESENT by Ursula K. Le Guin

““Fantasy, or Phantasy,” Auntie replies, clearing her throat, “is from the Greek phantasia, lit. ‘a making visible.’” She explains that phantasia is related to the verbs phantasein, “to make visible,” or in Late Greek, “to imagine, have visions,” and phainein, “to show.” And she summarises the earliest meanings of the word fantasy in English: an appearance, a phantom, the mental process of sensuous perception, the faculty of imagination, a false notion, a caprice, a whim.

Then, though she eschews the casting of yarrow stalks or coins polished with sweet oil, being after all an Englishwoman, she begins to tell the Changes—the mutations of a word moving through the minds of people moving through the centuries. She shows how fantasy, which to the Schoolmen of the late Middle Ages meant “the mental apprehension of an object of perception,” that is, the mind’s very act of linking itself to the phenomenal world, came in time to signify just the reverse: an hallucination, or a phantasm, or the habit of deluding oneself. And then the word, doubling back on its tracks like a hare, came to mean the imagination itself, “the process, the faculty, or the result of forming mental representations of things not actually present.” Though seemingly very close to the Scholastic use of the word, this definition of fantasy leads in quite the opposite direction, often going so far as to imply that the imagination is extravagant, or visionary, or merely fanciful.

So the word fantasy remains ambiguous, standing between the false, the foolish, the delusory, the shallows of the mind, and the mind’s deep connection with the real. On this threshold it sometimes faces one way, masked and costumed, frivolous, an escapist; then it turns, and we glimpse as it turns the face of an angel, bright truthful messenger, arisen Urizen.

Since the compilation of my Oxford English Dictionary, the tracks of the word have been complicated still further by the comings and goings of psychologists. Their technical uses of fantasy and phantasy have influenced our sense and use of the word; and they have also given us the handy verb “to fantasise.” If you are fantasising, you may be daydreaming, or you might be using your imagination therapeutically as a means of discovering reasons Reason does not know, discovering yourself to yourself.”

SPECIAL THANKS

Many individuals have contributed towards the realization of this exhibition. We want to thank Anna Fält for offering her voice and sensibility.

Marek Pluciennik for his availability and expertise in experimenting and realizing the translation of the digital animation to film. We express our gratitude to Kia and Stephan Svaetichin, for helping to find the storm in the digital archive, interpreting and translating the text from Swedish to English. Thanks to Lasse Vairio for borrowing the Eiki projector and the looper. Myrsky – Tuuli

Our thoughts and feelings go to the Baltic Sea, The Arctic Ocean, Nerkoonjärvi, Kallavesi, which are an endless source of inspiration.

We could not present our work without the input of the FMI and Åland Maritime Museum.

With the support of Arts Promotion Centre Finland (Taike).

Discover more from Emma Fält - drawing out loud

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.